At the end of last month, Prince Talal bin Abdul Aziz, son of the founder of Saudi Arabia and half-brother to its present king, made an astonishing call for reform. “We cannot use the same tools we have been using to rule the country [from] a century ago,” he told the Financial Times. “This region is roiling with turmoil and radicalism and the aspirations of a young population, and I’m afraid we are not prepared for that.”

The prince has long been a dissonant voice in a family that frowns on public dissidence, and has no decision-making power. But his words speak to a fundamental battle taking place behind the guarded walls of the kingdom’s palaces. Will King Abdullah’s tentative steps towards reform, attempting to take back control of the judiciary, education and the religious police (the notorious mutawa) from reactionary clerics, continue? Or will the king’s recent appointment of Prince Nayef, the arch-conservative interior minister, as deputy prime minister and third in line to the throne, bring them to a halt?

For the problem facing this absolutist monarchy, which has managed to function both as the custodian of the birthplace of Islam and as a US ally sitting on a quarter of the world’s proven oil reserves, is not its immediate overthrow. (It has already seen off a proto-insurgency by al-Qaeda followers.) It is that the very basis of the House of Saud’s legitimacy, the fusion of temporal and religious power which forms the bedrock of the Saudi state, rests on its alliance with the House of Ibn Abdul Wahhab. And Wahhabism, the puritan faith formulated by this 18th-century religious reformer, is, in its essentials, the totalitarian creed espoused by Osama Bin Laden to justify his murderous jihad.

For many years the Saudi ruling family, which is also dependent for survival on its 64-year-old alliance with the US, managed to keep any difficulties caused by its reliance on these two radically opposed sources of support concealed behind a brittle facade of modernity. All this began to change, however, after 11 September 2001.

At first the al-Saud were in denial that 15 of the 19 hijackers were their countrymen, and that the attackers had been inspired by Bin Laden, a member of one of the kingdom’s leading merchant families. A year later, Prince Nayef was still insisting to a Kuwaiti newspaper that the attacks were a Zionist plot. When five western oil executives were killed at Yanbu, the Red Sea port, on 1 May 2004, then Crown Prince Abdullah said he was “95 per cent certain” that Zionists were behind it. Such attacks turned international opinion against Muslims: so, what other explanation could there be?

Once the jihadis turned their gunsights on the heart of the kingdom, however, the al-Saud began to accept the possibility of there being other culprits. The turning point came with the 29 May 2004 attack at al-Khobar in the Eastern Province. This is the region that contains the largest oil deposits in the world and is, in addition, the homeland of Saudi Arabia’s persecuted Shia minority. Islamist gunmen attacked two foreign oil company office blocks and an expatriate enclave, killing three Saudi and 19 foreign civilians as well as nine Saudi policemen. They sought out Christian, Hindu and Buddhist “infidels” to murder, while setting Muslim hostages free. As in Yanbu that same month, they were able to mount the spectacle of dragging the body of a westerner for more than a mile, spitting slogans as they went. Even though the attack turned into a siege, with Saudi security forces ringing the compound and commandos landing on the roof of a building where the gunmen were holding more than 40 hostages, three of the attackers were able to, or allowed to, escape.

The authorities finally had to acknowledge that al-Qaeda, incubated in good part by the fanatical Wahhabism the al-Saud imposed as the kingdom’s sole creed, was their problem, too. As the slaughter at al-Khobar was continuing, the then crown prince, now King Abdullah, vowed to crush “this corrupt and deviant group” in Saudi society. “Those who keep silent about the terrorists will be regarded as belonging to them,” he warned. The implication was that nothing less than a seismic reformation of the House of Saud’s relationship with the Wahhabi clerical establishment was required-a reforging of the historic agreement that is the foundation stone of the Saudi state.

This is, in fact, the third time the House of Saud has set up a state in peninsular Arabia. The epic begins in the mid-18th century, when an emir from the Nejd in central Arabia, Sheikh Muhammad Ibn Saud, took in an itinerant preacher by the name of Sheikh Muhammad Ibn Abdul Wahhab. In 1744, the compact between the two houses was sealed by the marriage of al-Saud’s son and Ibn Abdul Wahhab’s daughter. This combination of Islam and the al-Saud has formed the basis of the Saudi kingdom ever since. Its essential promise is to banish chaos and darkness-an echo of the pre-Islamic jahiliyya, or epoch of ignorance, that God sought to end through his revelation to the Prophet Muhammad-and substitute order, both human and divine.

By this time, the al-Saud had become oasis settlers. Increasingly populous and “detribalised”, they were obliged to find an alternative formula to build up their political and military strength, both to resist the predatory tribes and to press their ambitions. The alliance with Ibn Abdul Wahhab gave them just that: the magic ingredients of religious reform and jihad -a holy war to reclaim the peninsula of the Prophet Muhammad and the birthplace of Islam for true believers.

Abdul Wahhab espoused probably the most literalist, rigorous, antique and exclusivist interpretation of Sunni Muslim orthodoxy ever attempted as a form of governance. The Wahhab-Saud forces came to be known as Wahhabis, but often refer to themselves as the Ahl al-Tawhid, people of the oneness (of God). They regard any apparent deviation from monotheism-particularly evident to them in the practices of the Christians and the “idolatrous” and “rejection-ist” (Rafadah) Shia Muslims, for whom they reserved the lowest circle of hell-as infidel or apostate. This (in the strict sense of the word) totalitarian creed anathematised all other beliefs as illicit. It defined everyone else as “the Other”, drawing up as broad a definition of “non-believers” as has ever been devised. Wahhabism thus provides limitless sanction for jihad (making it hard for jihadis or their victims to understand how al-Qaeda, as the al-Saud insist, is in any way “deviant” from this orthodoxy).

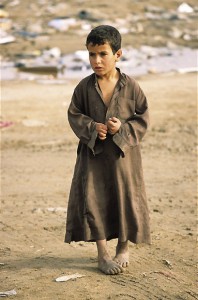

The Wahhabi claim is to have found Arabia in a tribal stew of idolatry and chaos, war and pillage, ignorance and vice. In effect, the Wahhab-Saud forces claim to have ended the second Arabian jahiliyya or age of ignorance. If true, that would put them on a par with the Prophet himself- a heady boast indeed. In fact, Saudi-Wahhabi propaganda is a mirror image of the orientalist discourse about the Hobbesian fate from which the west saved the east. It is a self-serving myth to justify the hegemony of the al-Saud and the Nejd over a regionally and religiously diverse nation, which was unified by force only after King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud fought 52 battles across a 30-year war of conquest, ending in 1932. Tawhid came to mean not just the “oneness” of God but the oneness of Arabia under Saudi hegemony.

In return for this religious cover, the Wahhabi clerical establishment was given decisive social control, not only over religion and public comportment, but also over education and justice. Above all, it derived power from conferring legitimacy on the Saudi rulers, who had now named the land of the Prophet after themselves. The politico-religious symbiosis of the House of Ibn Saud and the House of al-Sheikh, as it is now known, built the world’s first modern Muslim fundamentalist state.

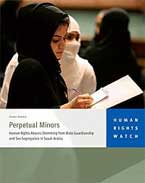

The state created by Ibn Saud has remained essentially static, while its subjects have been dragged into a modernity that rests on the shakiest foundations, imported like the air-conditioners that cool the gleaming malls and gated residential compounds. Within loudspeaker distance of a fire-and-brimstone mosque in Riyadh, close to the hotels where I have stayed many times, a shimmering mall houses a Harvey Nichols emporium with an outlet for La Senza, the lingerie chain. It is identical, in all respects except the gaudier range, to a similar shop anywhere else. But there is one fundamental difference. Because women may not mix with men outside their family and are kept in a mixture of seclusion and segregation, it follows that they cannot work in a lingerie boutique-which is therefore staffed entirely by men.

Saudi businesswomen, who operate with signal success but in a more or less separate environment from men, have increasingly been calling for a boycott of these kinds of arrangements, which are beyond satire.

A similar absurdity arises from the ban on women driving, which in practice has required the importation of more than a million foreigners to serve as drivers. In other words, a prohibition supposedly intended to keep women from temptation by denying them any independence leads to them being thrown into. daily contact with male strangers. Only a society that has living memory of the social conventions of slavery could be capable of countenancing such a paradox.

But it is probably in the field of education that this schizophrenia is most vividly and wrenchingly lived out. On the one hand, Saudi Arabia has an educated middle class, almost one million of whom have studied abroad. The kingdom has schooled its girls for nearly two generations. Saudis often have an intellectual depth to them that is less readily encountered in many Arab countries, where political and commercial pressures have debased and ground down the currency of ideas to convenient and remunerative cliche and myth. “There is something curiously uncalloused about the Saudis,” says a veteran diplomat to the kingdom.

But then turn to school textbooks, drawn up under the authority of the Wahhabi establishment. These drill into impressionable young Saudi minds the religious duty to hate all Christians and Jews as infidels, and to combat all Shias as heretics. A theology text for 14-year-olds, for instance, states that “it is the duty of a Muslim to be loyal to the believers and be the enemy of the infidels. One of the duties of proclaiming the oneness of God is to have nothing to do with his idolatrous and polytheist enemies.” The history textbooks typically emphasise the al-Saud hegemonic myth, burying any attempt to weave regional specificity or religious breadth into national identity under a suffocating narrative of Nejdi supremacy and Saudi redemption.

“It is really not very difficult to understand how we got to where we are,” says one reformist intellectual, asking rhetorically if there was any difference between the sectarian bigotry of Osama Bin Laden and the intolerant outpourings of the Wahhabi establishment. Saudi Arabia is a laboratory for jihad-that is its strategic dilemma.

While mosques and classrooms continue to spew out this fanaticism, Saudi Arabia has also been exporting these ideas for decades. Just during the reign of the late King Fahd, Riyadh claimed to have established 1,359 mosques abroad, along with 202 colleges, 210 Islamic centres and more than 2,000 schools. In addition, it episodically supported pan-Islamist movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood and sponsored jihad abroad from Afghanistan to Bosnia. Jihadis were able to establish a base in Iraq partly because Wahhabi proselytisers had established bridgeheads in cities such as Mosul in the final years of Saddam Hussein’s rule.

As king, Abdullah has introduced some incremental change. He has started rewriting textbooks, changing teaching methods and vetting teachers. He demanded the active co-operation of the clerical establishment in curtailing the flow of Saudi volunteers to Iraq. He has instituted de-radicalisation programmes for groups of jihadi prisoners who are willing to reintegrate into Saudi society. The king has also built tentative bridges to the Shias, and tried to foster a more pluralist conception of Islam.

In 2003, he launched a “national dialogue”, which held out the prospect of more open government, tighter financial controls on the royal family’s share of national wealth, greater rights for women, even the gradual introduction of elections. The king at least appeared to recognise the need for a more open society. But his brothers (the succession has always passed along the line of King Abdul Aziz’s elderly sons) did not share this view at all. No sooner was the national dialogue under way than Prince Nayef summoned dissidents to his office where, according to one reformer present, they were told: “What we won by the sword, we will keep by the sword.” Crown Prince Sultan said publicly, in March 2004, that the kingdom was not ready for an elected parliament, because voters might choose “illiterates”. Sheikh Saleh bin Abdulaziz al-Sheikh, then minister of Islamic affairs, rejected even the term “reform” as being pregnant with liberalism and licentiousness.

It is inescapable, however, that the al-Saud need to curb the corrosive power of the religious establishment and lead the kingdom towards a form of modernity that its religious heritage can sustain. And the most feasible way forward is to enlist Islamist progressives.

This loosely connected group of Islahiyyun or “reformers” has rediscovered the thinking of Islamic revivalists and reformers of more than a century ago, and turned it into a devastating critique of Ibn Abdul Wahhab.

Encouraged by Abdullah, the newspaper al-Watan (the nation, or homeland) became a forum for this debate, as did internet discussion groups, such as Muntada al-Wasatiyya, set up by the dissident Islamist Mohsen al-Awajy.

This still embryonic force has already achieved three major changes. First, the groups have presented their demands collectively, instead of petitioning individually at the majlis or court of the prince. The turning point was a 2003 petition signed by leading Islamist reformers and liberals. Second, the document proposed allowing diversity in matters of faith and politics-in a country where uniformity on both has long been imposed. And third, it broke the taboo about speaking against Wahhabism, and implied that it was this distorted form of Islam that was preventing Saudi Arabia from becoming a successful modern state all its citizens could easily support.

It is important to realise that the petition, titled “A vision for the present and future of the homeland”, draws on sources of renewal that are and will remain Islamic and, in important ways, Islamist. However alien this fusion of religion and politics may seem to secular westerners, it is key to any possibility of change, because it provides reformers with an authenticity and a legitimacy that deflects charges of foreign influence and intrusion. Sheikh Abdulaziz al-Qassim, a former Saudi judge and reformer, is an authority on this. “Al-Qaeda and the clergy are essentially doing the same thing in different ways-putting pressure on the House of Saud for being less devout than it should be. This paralyses reform,” he tells me. “The only way out is to dilute the link with Wahhabi fanaticism.

“The only way forward is to win the legitimacy of society itself- through political reform that does not depend on the approval of the clergy. If you make society part of reform you can overcome the clergy. It is the only way.”

The demands of the Islamist reformers include free elections, freedom of expression and association, an independent judiciary, a fairer distribution of wealth, and a clearer foreign policy arrived at through open debate-in short, a constitutional monarchy, if nowhere near a bicycling monarchy. “We are limiting our demands to very specific issues, and reiterating the al-Saud’s right to stay at the top of the tree,” says Mohsen al-Awajy. “They think it’s for tactical reasons, but the fact is there is no real alternative.”

Just how fundamental it is that liberals and Islamists take on Wahhabism cannot be overstated. But the liberals are an infinitesimal minority, tainted in the eyes of the masses with corruption and decadence. As one senior prince puts it, with a certain melancholy: “We liberals sit around a bottle of scotch and complain to each other, and then, the next morning, do nothing. Yet if we don’t get real progress, economically, socially and politically, we are going to be in a terrible mess in five to ten years.”

He, at least, shows an awareness alien to much of a bloated royal family that affects not to understand where a privy purse ends and a public budget begins, and continues to squander fabulous public wealth. Military spending, for example, is about three times the average for a developing country and is used as a mechanism for distributing power and wealth within the top ranks of the House of Saud-which is more than 5,000 princes strong.

No wonder that it is the Islamist reformers, numerically and ideologically, who are the real force for change. They can credibly argue that they intend no separation between mosque and state, but a redefinition of the relationship between the al-Saud and the al-Sheikh.

“Saudi Arabia has to be an Islamic state; it is the birthplace of Islam. The question is which Islam?” says Jamal Khashoggi, editor of al-Watan and adviser to Prince Turki al-Faisal, the former Saudi intelligence chief and ambassador to Washington and London. “The alliance should be between the state and Islam, not between the House of Saud and the House of al-Sheikh.”

Awajy, whose candour lost him his job as a university professor, argues: “The contract between the two houses is no longer in the interests of the Saudi people; if we tolerated it in the past it does not mean we will in the future. Real reform cannot take place within the Wahhabi doctrine.”

The Wahhabi establishment has pumped the poison of bigotry into the Saudi mainstream throughout the existence of the kingdom. After the attacks of 11 September 2001, it became impossible to ignore that its ideas and al-Qaeda’s were pretty much the same. It is hard to imagine how the House of Saud will survive unless it breaks decisively with these ideas. Or, as one Saudi reformer put it: “If this clerical establishment is incapable of imagining the solutions we need to modern problems, then the answer is clear-we have to find another establishment.”

By David Gardner