From its inception in 1987, Hizbullah al-Hijaz was a cleric-based group aligned with Iran, modeling itself on the Lebanese Hizbullah. It advocated violence against the Saudi regime and carried out several terrorist attacks in the late 1980s. Due to an improvement in Saudi-Iranian relations, it shifted its activities more towards non-violent opposition. Although opposed to negotiations with the Saudi leadership, it benefited from a general amnesty in 1993. After Hizbullah al-Hijaz was blamed for the Khobar bombings in 1996, most of its members were arrested. The crackdown and the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement following the accession of Muhammad Khatami in 1997 led to the disappearance of the organization, although its clerical leaders continue to be popular in parts of the Eastern Province. While the Khobar bombings have been discussed widely, only a few academic studies deal partially with Hizbullah al-Hijaz. The founding of the organization, its ideology, its role in Saudi-Iranian relations, and the activities of its members before and after the Khobar bombings have never been the subject of a distinct study.

Saudi Shi’a Clerics in Qom: The Formation of Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz

In the 1970s, a group of Saudi Shi’a, who were studying in Najaf with Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr, became acquainted with Khomeini’s teachings. After the Iranian Revolution they moved to Qom, where, in the mid-1980s, they formed Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz, which later became part of Hizbullah al-Hijaz. The clerical wing of the Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz operated out of the Hawza al-Hijaziyya (Hijazi seminary) in Qom. Their names indicate that, like Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, they used the term “Hijaz” for the whole of Saudi Arabia to undermine the legitimacy of the Al Sa’ud. They also called themselves Hijazin or Khat al-Imam, the line of Imam (Khomeini), the name by which the group is still referred to colloquially in Saudi Arabia. Although there is a small Shi’a community in Medina, the founders of Tajamu’ and Hizbullah come from the Eastern Province, mainly from al-Ahsa, Safwa, and Tarut.

- Husayn al-Radi

The biographies of the founders of the movement share some similarities: Husayn al-Radi was born in 1950/51 in ‘Umran in al-Ahsa. He studied in Najaf with Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr, and after the latter was killed in 1980, he moved to Qom. There he continued his studies with Hossein Montazeri and then became the supervisor of the Hawza for the Saudi students (al-Hijazin). In this position, he developed what he calls “special relationships” with Ayatollahs Hossein Montazeri - at that time the designated successor of Ayatollah Khomeini - and Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi. Shahroudi was also a disciple of Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr and left Najaf for Qom in 1979 to teach in the Hawza. Another leader of Tajamu’, Hashim al-Shakhs, was born in 1957 into a famous clerical family in al-Ahsa. His relative, Sayyid Muhammad Baqir al-Shakhs, was an early politically active Shi’a cleric and co-founder of the “Society of ‘Ulama’ in Najaf” in 1959/60. This connection facilitated his move to Najaf in 1972, where he became a follower of Ayatollah Khomeini.

- Hashim al-Shakhs

In the late 1970s, al-Shakhs returned to Saudi Arabia and started preaching in the village of Qarah in al-Ahsa. In the early 1980s, he went to Qom to study with Hossein Montazeri and to teach in the Hawza. It was only in Iran in the 1980s that he became politicized. Crucially, al-Shakhs and several other cadres of Hizbullah al-Hijaz, such as ‘Abd al-Karim al-Hubayl and ‘Abd al-Jalil al-Maa, did not take part in the Shi’a uprising of 1979/80 in the Eastern Province and remained in Saudi Arabia for a while after the uprising. Just days after the occupation of the Grand Mosque of Mecca by a group of Sunni rebels led by Juhayman al-‘Utaybi, the Shi’a in the Eastern Province staged Muharam rituals in public, defying a ban on public Shi’a processions in place since 1913. The instigators of this uprising were a network of young Islamists led by Hasan al-Safar and Tawfiq al-Sayf. They were the leaders of the Saudi branch, founded in 1975, of the Movement for Vanguards Missionaries (MVM), which worked under the spiritual guidance of Ayatollah Sayyid Muhammad Mahdi al-Shirazi (1928-2001). Tens of thousands took to the streets between November 26 and 30, 1979 and clashed with the National Guard, leading to around two dozen fatalities. On the eve of the demonstrations, the group adopted the name Munazama al-Thawra al-Islamiyya fi al-Jazira al-‘Arabiyya (Islamic Revolution Organization in the Arabian Peninsula: IRO). Although some later members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz, such as ‘Ali ‘Abdallah al-Khatim from Tarut, participated in the uprising, the “Intifada,” as the uprising was termed by the IRO, does not feature heavily in the discourse of Hizbullah al-Hijaz.

After the uprising, several hundred young Saudi Shi’a were brought to the Hawza al-Imam al-Qa’im of the MVM in Tehran. Immediately after the Iranian Revolution, the MVM and its leaders such as Muhammad Taqi al-Mudarrasi were very close to the new Iranian leadership and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Muhammad al-Shirazi also had good relations with Khomeini, and he and the cadres of the MVM moved to Iran. Iranian support for the Shi’a movements in Iraq and the Gulf was implemented through the Office of the Liberation Movements, created in the early 1980s and first headed by Mohammed Montazeri and then Mehdi Hashemi. The political theory of Muhammad al-Shirazi and the MVM was quite close to Khomeini’s notion of velayet-e faqih (the guardianship of the jurisprudent), although al-Shirazi favored the theory that not a single cleric, but a council of scholars should govern the Islamic State (hukumat al-fuqaha’/shurat al-fuqaha’). Therefore, al-Shirazi had expected a bigger role in post-1979 Iran, and relations between him and Khomeini deteriorated in the early 1980s. He also continued to compete with Khomeini for the post of marja’ al-taqlid - the post of highest ranking authority for Shi’a Muslims.

- Muhammad al-Shirazi

The MVM and its Iraqi branch, the Islamic Action Organization (Munazama al-‘Amal al-Islami), often acted rather autonomously, which led to conflicts with the Iranian government. The MVM saw armed struggle as a legitimate political tool and had a military wing, which was active in Bahrain until its coup attempt was foiled in December 1981, and in Iraq under Saddam. Although there was no such military branch for Saudi Arabia, the Iranian authorities repeatedly pressured the MVM and the IRO to intensify military efforts in the Gulf states. After the bloody crackdown on the “Intifada” in 1979/80, the MVM thought that military action was of little use in the Saudi case and rejected bombings and assassinations there. Yet, a number of Saudi Shi’a fought in the MVM’s military branches or opted to fight on the Iranian side in the Iran-Iraq War.

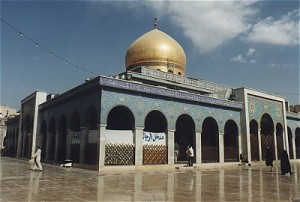

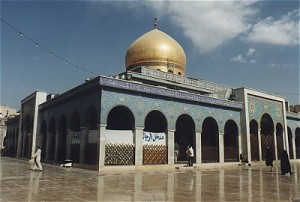

In contrast to the MVM and the IRO, the Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz initially did not have a defined organizational structure and focused on religious activities and the propagation of the marja’iyya of Khomeini. From about 1985 onwards, members of Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz came to Sayyida Zaynab, a shrine city outside Damascus, in addition to the Eastern Province, and started preaching the virtues of Khomeini. Sayyida Zaynab was an important transnational hub for the Gulf Shi’a, especially the ones following Ayatollah Shirazi. In 1987, they started their first publication, al-Fath, under the name of Hijaz Students Group (Jama’ min Talaba al-Hijaz). Some lay activists also started to work with Tajamu’, although its leaders remained clerics.

- Sayyida Zaynab

Saudi-Iranian Rivalry over the Hajj and the Foundation of Hizbullah al-Hijaz

In the second half of the 1980s, Iran began to revise its policy of exporting the revolution, and the position of the MVM in Iran was severely weakened. The MVM was close to parts of the Iranian regime advocating the export of the revolution, namely Hossein Montazeri and Mehdi Hashemi. Yet, this faction was increasingly sidelined by people such as Sayyid ‘Ali Khamene’i and ‘Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who questioned the usefulness of this approach. The MVM was directly involved in the struggle between the different Iranian political factions, and a member of the MVM allegedly helped to leak the Iran-Contra Affair in late 1986. As a result, Mehdi Hashemi was executed in 1987, the Office of the Liberation Movements closed, and Hossein Montazeri was deposed in 1989 as the successor of Ayatollah Khomeini. Consequently, the MVM and the IRO had lost their main ally in Iran, and their leaders chose to leave Iran gradually. In addition, the Central Committee of the IRO made a decision in 1987 to soften its approach towards the Saudi regime after a general amnesty decreed by King Fahd. Thereafter, ordinary members of the MVM and the IRO began to be harassed by Iranian authorities. However, the IRO still had representatives in Tehran and Qom and maintained relations with the Iranians and with Hizbullah al-Hijaz.

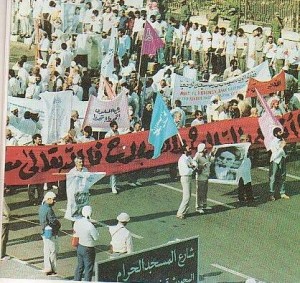

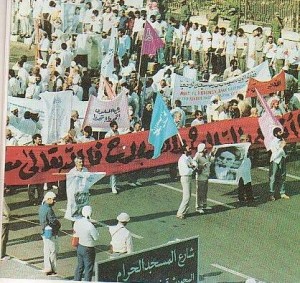

On July 31, 1987, over 400 people, most of them Iranian pilgrims but also many Saudi policemen, were killed and many more injured at a demonstration that led to a stampede outside the Great Mosque in Mecca during the Hajj. Iran and Saudi Arabia blamed each other for the clashes, leading to a severe worsening of Saudi-Iranian relations. Although the incident mainly involved Iranians, some had alleged links to Saudi Shi’a organizations. As a result, both countries sought to influence Muslim public opinion abroad and discredit the other party. The weak relations of the MVM and the IRO to the new centers of power in the Iranian regime, their refusal to carry out military operations in Saudi Arabia, and the Hajj incident in 1987 were the main reasons for the formation and the strengthening of Hizbullah al-Hijaz. Iran wanted to have small, controllable organizations that could be used as pressure tools on the Al Sa’ud but would not endanger Iran’s foreign policy objectives.

- 1987 Mecca Demonstration

Founded in May 1987, Hizbullah al-Hijaz issued one of its first statements one week after the Hajj incident, vowing to stand up against the Saudi rulers. Among the founders of Hizbullah al-Hijaz were the leaders of Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz, Shaykh Hashim al-Shakhs, Shaykh ‘Abd al-Karim al-Hubayl, and ‘Abd al-Jalil al-Maa. From the beginning, Hizbullah al-Hijaz had two wings: one for religious and political activities - Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz - and another one for military tasks. Some members of the movement came from Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz, but others were members of the MVM that wanted to use violence against the Saudi regime and preferred the marja’iyya of Khomeini. Ahmad al-Mughasal, who came to be the head of the military wing of Hizbullah al-Hijaz, was a former member of the MVM and had studied at the Hawza Imam al-Qa’im in Tehran. Furthermore, some Saudi Shi’a students who had studied in the US, who belonged to later generations of members of the MVM, joined Hizbullah al-Hijaz. This led to tensions between Hizbullah al-Hijaz and the IRO, which had hitherto been the only Islamist Saudi Shi’a opposition group. Hizbullah al-Hijaz’s long-term political goal was the establishment of an Islamic Republic in the Arabian Peninsula after the Iranian model, and it advocated the overthrow of the Saudi regime through violence.

- Abd al-Karim al-Hubayl

Escalation , Violence, and a Gradual Improvement in Saudi-Iranian relations

After the Hajj Incident in 1987, “many supporters of the Islamic Republic among the Shi’a were willing to pursue military means to retaliate against the Saudi regime.” In August 1987, an explosion occurred at a petroleum facilty in Ra’s al-Ju’ayma. Although the government claimed that it was an accident, it was later ascribed to Hizbullah al-Hijaz. In March 1988, the Sadaf petrochemical plant in Jubayl was bombed, an incident for which Hizbullah al-Hijaz claimed responsibility. A Hizbullah cell with four members from Tarut had carried out the attack. One of them had been an employee at Sadaf, while another, al-Khatim, had fought with Hizbullah in Lebanon and had received military training. Several bombs also detonated at the Ra’s Tanura refinery and one allegedly failed to explode in Ra’s al-Ju’ayma. Widespread arrests occurred, and when the security forces confronted three members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz, several Saudi policemen were killed and injured. These three and another member of the cell were later publicly executed. The execution of the four was enabled by a fatwa from the Council of the Assembly of Senior ‘Ulama’ (Majlis Hay’a Kibar al-‘Ulama’) allowing the execution of dissidents convicted of “sabotage.” The IRO argued that the bombings were a response to Saudi assistance to Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War and that, while it did not claim responsibility for them, bombings were a natural continuation of the opposition’s activities. In response, Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz issued one of its first public statements, entitled “the execution of four fighters (mujahidin) in the Arabian Peninsula” and so did Hizbullah al-Hijaz. In addition, Ayatollah Montazeri condemned the execution while the Iranian Foreign Ministry issued a statement denying any links to the executed.

In response to this escalation, members of the IRO, leftist groups, and leaders of Hizbullah such as ‘Abd al-Karim al-Hubayl and Ja’far al-Mubarak were arrested. Four members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz were released in 1990 as part of a royal pardon but at least four other leaders remained in prison until 1993. Some Shi’a apparently blamed the opposition movements for the crackdown, and this was a reason for the IRO to abandon its revolutionary discourse.

Some members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz wanted to avenge the beheadings and assassinated several Saudi diplomats and agents abroad. It is possible that they were killing security officials that were trying to arrest and extradite them to Saudi Arabia. One report argues that the killings in October 1988 and January 1989 and the attempted killing in December 1988 targeted members of the Saudi Arabian intelligence services, working under diplomatic cover, who had been pursuing a group of about 20 Shi’a for their involvement in the bombings of oil installations in the Eastern Province.

Two groups, the Soldiers of Justice (Jund al-Haqq) and the Holy War Organization in the Hijaz, claimed responsibility from Beirut for an assassination in Bangkok in January 1989. The Holy War Organization in the Hijaz claimed that the killing was revenge for the execution of four of its members in Saudi Arabia, and Risalat al-Haramayn reported that an October 1988 killing in Ankara was also in retaliation for the executions in Saudi Arabia. Some sources assert that this was a new front organization made up of Lebanese and Saudi Shi’ites with links to Palestinian groups and factions inside Iran that were opposed to an Iranian rapprochement with Saudi Arabia. These two groups, probably related to the military wing of Hizbullah al-Hijaz, claimed responsibility - or were blamed - for the assassination of a Saudi diplomats in Ankara in October 1988 and in 1989, of wounding a Saudi diplomat in Karachi in December 1988 in addition to several bomb attacks in Riyadh in 1985 and in 1989.

In September 1989, 16 Kuwaiti Shi’ites were beheaded for smuggling explosives and placing them in the vicinity of Mecca’s Grand Mosque in July 1989. They were members of the group Hizbullah al-Kuwayt but were all Shi’a of Iranian or Saudi origin. Indeed, the family links between Shi’a from al-Ahsa and Saudi Shi’a emigrants to Kuwait are usually strong and continue to play a role in the development of Hizbullah networks in the Gulf. Some Shi’a from al-Ahsa were also arrested and members of Hizbullah al-Kuwayt and Hizbullah al-Hijaz jointly announced vengeance at a press conference in Beirut. In November 1989, the Holy War Organization claimed responsibility for the assassination of a Saudi diplomat in Beirut in revenge for the beheading of the 16 Kuwaitis and the four Saudis.

From the late 1980s onwards, several members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz travelled to Iran and Lebanon, where they likely received military training. They used Sayyida Zaynab in Syria as a hub for their travels to Saudi Arabia and for the recruitment of new members, who visited the shrine of Sayyida Zaynab on pilgrimage. Some Saudi Shi’a also fought with Lebanese Hizbullah against Israel in southern Lebanon.

Ideology and Propaganda: Risalat al-Haramayn

Saudi-Iranian relations gradually improved after the end of the Iran-Iraq War in August 1988, the death of Khomeini in June 1989, and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990. Iran had, however, an interest in continuing to promote anti-Saudi propaganda and establishing a hegemonic claim over Mecca and Medina as well as portraying itself as the patron of Saudi Shi’a. This caused Hizbullah al-Hijaz to focus more on political and propaganda activities, such as the publication of a journal, Risalat al-Haramayn (The Letter of the Two Holy Places [Mecca and Medina]), at the expense of assassinations and attacks. It was published by the al-Haramayn Islamic Information Center and Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz from 1989 to 1995 in Beirut, although from 1991 it also had an office in London. The outreach of the journal was supposed to be the whole umma. It focused on the legacy of Ayatollah Khomeini, and published statements by Hizbullah al-Hijaz and Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz. It was mainly written by a new group of non-clerical activists referred to as the effendiyya in Shi’a circles. Many of the activists behind Risalat al-Haramayn had been educated by the MVM in Kuwait and then in Tehran. Members of Iraqi and Lebanese Hizbullah also wrote in the journal.

Anti-Saudi propaganda, the creation of a martyrdom mythology, and the links to other movements were some of the main focuses in the journal. The first martyrs of Hizbullah al-Hijaz were the four “mujahidin” that were executed in 1988. As three of the four and some of the Saudis who fought on the Iranian side in the Iraq-Iran War were from the village of al-Rabia’iya on Tarut Island, this village was frequently described in the journal as the archetypical revolutionary village. The four also entered the martyrdom discourse of the IRO, and certain contemporary oppositional publications and websites still remember them as the “four martyrs.” The publication also tried to promote the legacy of Shi’a clerics in Saudi Arabia, something which Hashim al-Shakhs continued in his four-volume work on the Shi’a clerics from al-Ahsa.

- Sayyid Hasan Nasrallah

In autumn 1989, members from the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (SCIRI) and Lebanese Hizbullah gave speeches praising the four martyrs in Sayyida Zaynab outside of Damascus while Sayyid Hasan Nasrallah delivered a similar speech in Qom. In Baalbek, one member of Tajamu’, Muhammad al-Mubarak, denounced the Saudi regime in the presence of a representative of the Iranian Embassy in Damascus. The journal also reported meetings between delegations of Tajamu’ with Lebanese Hizbullah and Khamene’i. This made clear that Hizbullah al-Hijaz was very well connected to and supported by Iran and Lebanese Hizbullah, among others.

A cleric of Hizbullah al-Hijaz argued that there is no difference between the Hizbullah groups “in Hijaz, Kuwait, Lebanon or any other place.”

In addition, the organization accepted Sayyid ‘Ali Khamene’i as Khomeini’s successor, and the clerics began to assume a leading role in Hizbullah al-Hijaz, following Khomeini’s doctrine of velayet-e faqih. Furthermore, the journal stated that “there is no doubt that our links with the Islamic Republic are very strong, because it is a base for all the liberators and revolutionaries in the world.”

The discourse of the movement became increasingly anti-American from 1990 onwards. Hizbullah al-Hijaz and Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz both declared in 1990 that the deployment of US troops to Saudi Arabia made jihad against the unbelievers a duty of Muslims. This discourse was, however, not unique to Shi’a Islamists; the deployment of US troops to Saudi Arabia was one of the main reasons for the rise of the Sunni Islamist opposition. To a certain extent, the discourse in Risalat al-Haramayn shifted more towards human rights and freedom of speech, although the IRO’s switch towards a discourse of democratization was much more pronounced.

“The Regime swallows the Opposition:” Hizbullah al-Hijaz Publicly Opposes the Agreement between the IRO and the Saudi Leadership in 1993

In autumn 1993, the Saudi regime and some leaders of the IRO reached an agreement to abandon the latter’s political activities in return for a general amnesty. On the regime’s side, the main reasons for this agreement were the regional crises which occured after the invasion of Kuwait and reports about a possible alliance of Sunni and Shi’a Islamists. The IRO negotiated in the name of all Saudi Shi’a opposition groups, including Hizbullah al-Hijaz and the leftists that were active in Syria and Iraq. Some argue that the negotiations were also intended to isolate Hizbullah al-Hijaz and that they were not asked to take part in the negotiations.They were informed about the negotiations by the IRO, but Hizbullah al-Hijaz argued that it would only negotiate if there were an end to sectarian discrimination and real gains for the Shi’a. Although some in the IRO had voiced similar demands, al-Safar and other leaders of the IRO agreed that these things could not be done immediately by the government. Hizbullah al-Hijaz argued that the opposition would lose its strength if it ceased its publications and returned to Saudi Arabia, where it would be under tight supervision by the security services. The movement stated that the negotiations were intended to play out the Shi’a opposition against the Salafis. In addition, Hizbullah al-Hijaz would only change its strategy if the Shi’a were to be recognized as an official sect by the government. It vowed to continue on the path of jihad and revolution and invoked the example of the four martyrs of 1988. A reason for this official opposition was the dissatisfaction of the Iranian regime with the negotiations.

- Hasan al-Safar

Eventually, the agreement included the release of all Saudi Shi’a political prisoners, many of whom were members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz, and thus most members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz and Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz returned to Saudi Arabia. They suspended the publication of Risalat al-Haramayn in 1995 but - unlike the suspension of the IRO’s publication al-Jazira al-‘Arabiyya - this was not a condition of the agreement as the government thought its impact was limited. Iran apparently tried to persuade the members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz that it had played a role in the release of their prisoners, and that it was a result of the rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia. In the following years, the Hizbullah trend gained in prominence amongst those former activists and ordinary Shi’a that were dissatisfied with the agreement or had opposed it from the beginning.

After their return to Saudi Arabia in 1993 and 1994, many members focused on religious and social activities. The clerics became imams in their local mosques and started teaching in the Hawza in Mubarraz or Qatif. Ja’far al-Mubarak was released from prison in the summer of 1993 but was subject to intense surveillance and was not allowed to perform Friday prayers. This was used as an example in the movement literature that the opposition should not trust the Saudi regime. He returned to a leadership role in Hizbullah al-Hijaz and eventually became an imam in Safwa. Hashim al-Shakhs also became imam in a local mosque in his native village of al-Qarah, and like other clerics of Hizbullah al-Hijaz, started to work as a local representative of Ayatollah Khamene’i, gaining an income from the religious khums tax.

- Ja’far al-Mubarak

The Khobar Bombings: Accusations, Arrests, and the Disappearance of Hizbullah al-Hijaz

On June 25, 1996, a tanker truck filled with several tons of TNT exploded near the Khobar Towers housing compound for the US Air Force in Dhahran, killing 19 US soldiers and injuring hundreds of others. Shortly afterwards, the Saudi government started to blame Hizbullah al-Hijaz for the attack and arrested hundreds of Islamists, both Sunni and Shi’i. Nearly everyone who was loosely affiliated with Hizbullah al-Hijaz was arrested in the crackdown. The prisoners included its main religious and political leaders such as Hashim al-Shakhs, Ja’far al-Mubarak, ‘Abd al-Karim al-Hubayl, and Husayn al-Radi. Many were tortured and remained imprisoned for years. Sympathizers with the movement were arrested for the possession of books by Khomeini or Fadlallah or because they had attended mosques where Hizbullah clerics preached. Although several reports of the investigation were published, there were tensions between Saudi and American investigators. Some claim that strong evidence for Iranian involvement would have been used as a pretext for war against Iran, something the Saudis did not want. This would have destabilized the whole region and probably involved the redeployment of more American troops to Saudi Arabia. It took several years before the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was granted access to the suspects and almost five years until they were indicted in the US. The accused included Ahmad al-Mughasal, the alleged head of the military wing of the Saudi Hizbullah, Hani al-Sayigh, and ‘Abd al-Karim al-Nasir, whom the indictment described as the leader of Saudi Hizbullah. Especially after September 11, 2001, the theory that al-Qa’ida was involved in or responsible for the attack gained in prominence. Although Usama bin Ladin has repeatedly applauded the Khobar attacks, he did not take responsibility for them, and Thomas Hegghammer states that al-Qa’ida did not have the technical skills at the time to carry out such a large-scale attack. He also dismisses the idea of cooperation between al-Qa’ida and Iran.

In June 2002, a Saudi official said that a number of Saudis arrested after the Khobar bombings had been convicted110 and that nine Shi’a blamed for involvement in the preparation and the execution of the bombings remained imprisoned in SaudiArabia.

As a response to the indictment and the trials, al-Haramayn Islamic Information Center published a long report on the Khobar Bombings in June 2002. It attempts to prove that the investigations were flawed and implies that Hizbullah al-Hijaz was not responsible. In addition, it claims that blaming Saudi Shi’a and Iran was part of the American and “Zionist” agenda. The report implies that statements by Hizbullah al-Khalij, or “Saudi Hizbullah,” claiming responsibility for the attack, which appeared in Western and Arab media, are forgeries. The report states that although Iran and Lebanese Hizbullah had expanded to the Gulf countries, an organization called Hizbullah al-Khalij is not known. It adds that two other organizations also claimed responsibility for the bombing, while reproducing statements by Iran, Lebanese Hizbullah, and Hizbullah al-Hijaz rejecting any involvement in the attack. According to the report, the absence of Ja’far al-Shuwaykhat from the indictment is another major flaw. Al-Shuwaykhat was a student in the Hawza in Qom and was arrested in 1988 upon his return to Saudi Arabia. After six years in prison, he was released and went to Syria. A biography of the “martyr” al-Shuwaykhat posted on a homepage associated with the Hizbullah networks claims that he was involved in a number of military operations, that his main enemy was the Americans, and that he rejoined his former group in Syria after being released from prison. After the Khobar bombings, he was arrested by Syrian intelligence, apparently on the request of the Saudi government, but died in a Syrian prison only days later. Several interviewees pointed out that he could have provided vital information and that his sudden death and the absence of his name in the indictment were suspicious.

- Ja’far al-Shuwaykhat

The report sees the American troops as occupiers and implies that the authors see American troops as a legitimate target. It urges the Americans to think about the reasons for the bombings, namely their occupation of Muslim lands and their arrogance towards other people. In a statement released in late 1996, Hizbullah al-Hijaz rejects any responsibility for the bombings but calls the US the “biggest satan.” A statement published after the US indictment in 2001 argues that “although we refute this indictment as a whole and in detail, we will continue on the path of Jihad until the expulsion of all occupiers from the land of the Arabian Peninsula.”

Hizbullah al-Hijaz’s ideology would, therefore, have permitted an attack on American soldiers in Saudi Arabia. In addition, members of Saudi Hizbullah wanted to continue an armed struggle against the Saudi regime as well as against its main backer, the US. They also may have wanted to demonstrate their strength and disapproval of the 1993 accord, hoping that the repression after an attack on a US target would be less harsh than after attacking the Saudi government directly. However, the Khobar bombings were much more sophisticated than earlier operations by the group. It is also puzzling why the group should, after an absence of attacks for over six years, return to violence as a political tool. Given the close relations with Lebanese Hizbullah, it seems plausible that, if Hizbullah al-Hijaz was behind the attack, it would have needed Lebanese technical assistance. The connection to Iran is impossible to assess through an analysis of open source material, but a faction inside Iran opposed to the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement could have masterminded the attack. It is also possible that the military wing of Hizbullah al-Hijaz acted with Iranian or Lebanese support but without the knowledge of the clerics of Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al- Hijaz.

After the Khobar Bombings: Online Propaganda, Social Activism, and Clerical Authority

The virtual disappearance of Hizbullah al-Hijaz as an organization after 1996 is due to the arrest of most of its members and a general Saudi-Iranian rapprochement leading to a security agreement in 2001. After the Khobar bombings, Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed that while Saudi Arabia would not permit the US to launch attacks on Iran from the Kingdom, Iran would stop supporting Saudi Shi’a opposition activists. Although several of those accused in the indictment are believed to be in Iran, the agreement did not include the extradition of fugitives. On his historic visit to Saudi Arabia in 1998, ‘Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani planned to call for the release of the Shi’a arrested after the Khobar bombings.It is not clear whether this influenced the gradual release of many high- and middle-ranking members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz. Thereafter, they refrained from openly political activities and renounced violence as a political tool.

They focused more on social and religious activities such as the organization of marriages, pilgrimages to Mecca, and public festivities during Muharam and the birthdays of the Imams. Young Qatifis point out that former movement members are active in schools and other gathering places for the youth. Its current leaders include Shaykh Hashim al-Hubayl, Sayyid Kamal al-Sada, and Shaykh Hasan al-Nimr, who hosts a diwaniyya in Dammam. Due to the improvement of Saudi-Iranian relations, the religious activities of the pro-Iranian clerics are increasingly tolerated. There continue to be roughly 200 Saudi students in Qom, although the majority of them do not follow Khamene’i, but rather follow Ayatollah ‘Ali al-Sistani. The religious connection to Iran, however, does not imply membership in the political organization Hizbullah al-Hijaz. Until 2008, Dr. ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Fadli was considered the main representative of Ayatollah Khamene’i in Saudi Arabia. Originating from al-Hasa, Al-Fadli had been one of the founding members of the Dawa Party in Iraq. He later became the head of the Arabic language department at King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz University in Jeddah and a follower of Ayatollah Khomeini. He is a mujtahid and a prolific writer and some consider him to have been a candidate for a local marja’iyya.

- Dr. ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Fadli

Some former leaders of Hizbullah al-Hijaz such as ‘Abd al-Karim al-Hubayl have started a gradual rapprochement with the government, emulating the IRO. Hasan al-Nimr encouraged some supporters of Hizbullah al-Hijaz to stand in the municipal elections of 2004/5, although they failed to win a seat. Other former leaders of the Hizbullah, such as Husayn al-Radi, have participated in the National Dialogue. Contrary to the IRO, the Hizbullah has always emphasized the role of the clergy and lacks a mass following. On the other hand, some of the highest ranking Saudi Shi’a scholars such as ‘Abd al-Hadi al-Fadli and Hashim al-Shakhs - both considered to be mujtahids - are leaders of the Hizbullah. When the system of the Shi’a courts in the Eastern Province was reorganized in 2005, a former supporter of Hizbullah al-Hijaz, Ghalib al-Hamad, was briefly appointed as the Shi’i judge of Qatif. This shows that the Saudi regime thought it was useful to co-opt certain members of Hizbullah al-Hijaz with public posts and to allow its religious activities, including the collection of khums money for Khamene’i. The “al-Fajr cultural website” serves as a platform for their moderated discourse and the propagation of the marja’iyya of Khamene’i. It publishes the Friday prayers of Hashim al-Shakhs and others, provides guidance on religious matters and, since early 2008, publishes a journal dedicated to the spirit of Imam Husayn and Imam Khomeini.

The confrontational discourse of Hizbullah al-Hijaz is only present on the website of al-Haramayn Islamic Information Center. It seems that those people responsible for this website are outside of Saudi Arabia and that they no longer form one group with those former leaders that returned to Saudi Arabia. The Center, however, continues to issue statements by, amongst others, Hizbullah al-Hijaz, Tajamu’ ‘Ulama’ al-Hijaz, and the “Committee for the Defense of Human Rights in the Arabian Peninsula,” while also digitizing Saudi Shi’a opposition publications such as Risalat al-Haramayn.

Recent Hizbullah al-Hijaz statements dealt with Saudi Arabia’s condemnation of Lebanese Hizbullah’s activites in 2006 or the assassination of ‘Imad Mughniyya, the military leader of Lebanese Hizbullah. Some supporters of Hizbullah al-Hijaz started to express themselves through support for Lebanese Hizbullah. In July and August 2006, several demonstrations in support of Lebanese Hizbullah occurred in Qatif and surrounding areas and security forces arrested dozens. However, the demonstrations did not only involve supporters of Hizbullah but also other political groupings.

But the group also comments on domestic Saudi matters. In 2005, Hasan al-Safar implied in an interview that Hizbullah al-Hijaz had been part of the 1993 agreement and that it had abandoned its revolutionary discourse and organizational activities thereafter. Hizbullah countered with a long statement condemning the rapprochement between the IRO and the Saudi government and stating that its main political goals were “the military, economic and political liberation of our homeland (the Arabian Peninsula) from the American-Western Occupier” and the downfall of the Al Sa’ud. From spring 2008 onwards, a new weekly news survey - al-Rasid al-Sahafi - concerning Saudi Shi’a issues was published on the website. It also focuses on, for example, Saudi involvement in Lebanon, praising Hizbullah’s activities there, while reproducing statements by Khamene’i and Fadlallah.

Conclusion

From its inception, Hizbullah al-Hijaz has advocated armed struggle against the Saudi regime. After the Hajj in 1987 Iran wanted to retaliate against Saudi Arabia and created Hizbullah al-Hijaz as a pressure group that was integrated into the Hizbullah networks. Therefore, it was subject to changes in Saudi-Iranian relations, which partially explains the absence of attacks between 1989 and 1996 and its virtual disappearance after the Khobar Bombings. With the accession of Khatami as Iranian President, Saudi-Iranian relations ameliorated considerably, leading to a security agreement in 2001. Thereafter, most former members have abstained from politics but many are still deeply suspicious of the regime. In the local context, Hizbullah al-Hijaz has always positioned itself as the most radical Saudi Shi’a opposition group. So far, the Hizbullah trend has not managed to integrate itself into local Shi’a politics in the way the former leaders of the IRO have. Its former advocacy of violence, the political theory of velayet-e faqih, and the uncritical endorsement of the Iranian political system are the main reasons for its limited influence in contemporary Saudi Shi’a affairs. The Iranian model does not have the same appeal for Saudi Shi’a as it did in the 1980s. Yet, sectarian tensions in Saudi Arabia have increased following the clashes between Shi’a and Sunni pilgrims and riot police in Medina in 2009 and the subsequent demonstrations and arrests in the Eastern Province. It is not inconceivable that this broadens the appeal of groups like Hizbullah al-Hijaz that advocate an uncompromising approach towards the Saudi state.

By Toby Matthiesen