For three months, the Arab world has been awash in protests and demonstrations. It’s being called an Arab Spring, harking back to the Prague Spring of 1968.

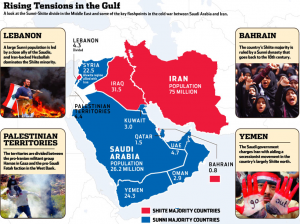

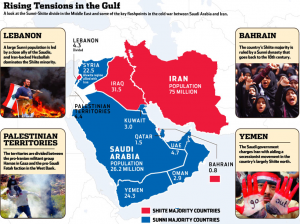

But comparison to the short-lived flowering of protests 40 years ago in Czechoslovakia is turning out to be apt in another way. For all the attention the Mideast protests have received, their most notable impact on the region thus far hasn’t been an upswell of democracy. It has been a dramatic spike in tensions between two geopolitical titans, Iran and Saudi Arabia.

This new Middle East cold war comes complete with its own spy-versus-spy intrigues, disinformation campaigns, shadowy proxy forces, supercharged state rhetoric—and very high stakes.

“The cold war is a reality,” says one senior Saudi official. “Iran is looking to expand its influence. This instability over the last few months means that we don’t have the luxury of sitting back and watching events unfold.”

On March 14, the Saudis rolled tanks and troops across a causeway into the island kingdom of Bahrain. The ruling family there, long a close Saudi ally, appealed for assistance in dealing with increasingly large protests.

Iran soon rattled its own sabers. Iranian parliamentarian Ruhollah Hosseinian urged the Islamic Republic to put its military forces on high alert, reported the website for Press TV, the state-run English-language news agency. “I believe that the Iranian government should not be reluctant to prepare the country’s military forces at a time that Saudi Arabia has dispatched its troops to Bahrain,” he was quoted as saying.

The intensified wrangling across the Persian—or, as the Saudis insist, the Arabian—Gulf has strained relations between the U.S. and important Arab allies, helped to push oil prices into triple digits and tempered U.S. support for some of the popular democracy movements in the Arab world. Indeed, the first casualty of the Gulf showdown has been two of the liveliest democracy movements in countries right on the fault line, Bahrain and the turbulent frontier state of Yemen.

But many worry that the toll could wind up much worse if tensions continue to ratchet upward. They see a heightened possibility of actual military conflict in the Gulf, where one-fifth of the world’s oil supplies traverse the shipping lanes between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Growing hostility between the two countries could make it more difficult for the U.S. to exit smoothly from Iraq this year, as planned. And, perhaps most dire, it could exacerbate what many fear is a looming nuclear arms race in the region.

Iran has long pursued a nuclear program that it insists is solely for the peaceful purpose of generating power, but which the U.S. and Saudi Arabia believe is really aimed at producing a nuclear weapon. At a recent security conference, Prince Turki al Faisal, a former head of the Saudi intelligence service and ambassador to the U.K. and the U.S., pointedly suggested that if Iran were to develop a weapon, Saudi Arabia might well feel pressure to develop one of its own.

The Saudis currently rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella and on antimissile defense systems deployed throughout the Persian Gulf region. The defense systems are intended to intercept Iranian ballistic missiles that could be used to deliver nuclear warheads. Yet even Saudis who virulently hate Iran have a hard time believing that the Islamic Republic would launch a nuclear attack against the birthplace of their prophet and their religion. The Iranian leadership says it has renounced the use of nuclear weapons.

How a string of hopeful popular protests has brought about a showdown of regional superpowers is a tale as convoluted as the alliances and history of the region. It shows how easily the old Middle East, marked by sectarian divides and ingrained rivalries, can re-emerge and stop change in its tracks.

There has long been bad blood between the Saudis and Iran. Saudi Arabia is a Sunni Muslim kingdom of ethnic Arabs, Iran a Shiite Islamic republic populated by ethnic Persians. Shiites first broke with Sunnis over the line of succession after the death of the Prophet Mohammed in the year 632; Sunnis have regarded them as a heretical sect ever since. Arabs and Persians, along with many others, have vied for the land and resources of the Middle East for almost as long.

These days, geopolitics also plays a role. The two sides have assembled loosely allied camps. Iran holds in its sway Syria and the militant Arab groups Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Palestinian territories; in the Saudi sphere are the Sunni Muslim-led Gulf monarchies, Egypt, Morocco and the other main Palestinian faction, Fatah. The Saudi camp is pro-Western and leans toward tolerating the state of Israel. The Iranian grouping thrives on its reputation in the region as a scrappy “resistance” camp, defiantly opposed to the West and Israel.

For decades, the two sides have carried out a complicated game of moves and countermoves. With few exceptions, both prefer to work through proxy politicians and covertly funded militias, as they famously did during the long Lebanese civil war in the late 1970s and 1980s, when Iran helped to hatch Hezbollah among the Shiites while the Saudis backed Sunni militias.

But the maneuvering extends far beyond the well-worn battleground of Lebanon. Two years ago, the Saudis discovered Iranian efforts to spread Shiite doctrine in Morocco and to use some mosques in the country as a base for similar efforts in sub-Saharan Africa. After Saudi emissaries delivered this information to King Mohammed VI, Morocco angrily severed diplomatic relations with Iran, according to Saudi officials and cables obtained by the organization WikiLeaks.

As far away as Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country, the Saudis have watched warily as Iranian clerics have expanded their activities—and they have responded with large-scale religious programs of their own there.

The 1979 Iranian revolution was a major eruption that still looms large in the psyches of both nations. It explicitly married Shiite religious zeal with historic Persian ambitions and also played on sharply anti-Western sentiments in the region.

Iran’s clerical regime worked to spread the revolution across the Middle East; Saudi Arabia and its allies worried that it would succeed. For a time it looked like it might. There were large demonstrations and purported antigovernment plots in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, which has a large population of Shiite Muslim Arabs, and in Bahrain, where Shiites are a distinct majority and Iran had claimed sovereignty as recently as 1970.

The protests that began this past January in Tunisia had nothing to do with any of this. They started when a struggling street vendor in that country’s desolate heartland publicly set himself on fire after a local officer cited his cart for a municipal violation. His frustration, multiplied hundreds of thousands times, boiled over in a month of demonstrations against Tunisian President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali. To the amazement of the Arab world, Mr. Ben Ali fled the country when the military declined to back him by brutally putting down the demonstrations.

Spurred on by televised images and YouTube videos from Tunisia, protests broke out across much of the rest of the Arab world. Within weeks, millions were on the streets in Egypt and Hosni Mubarak was gone, shown the door in part by his longtime backer, the U.S. government. The Obama administration was captivated by this spontaneous outbreak of democratic demands and at first welcomed it with few reservations.

In Riyadh, Saudi officials watched with alarm. They became furious when the Obama administration betrayed, to Saudi thinking, a longtime ally in Mr. Mubarak and urged him to step down in the face of the street demonstrations.

The Egyptian leader represented a key bulwark in what Riyadh perceives as a great Sunni wall standing against an expansionist Iran. One part of that barrier had already crumbled in 2003 when the U.S. invasion of Iraq toppled Saddam Hussein. Losing Mr. Mubarak means that the Saudis now see themselves as the last Sunni giant left in the region.

The Saudis were further agitated when the protests crept closer to their own borders. In Yemen, on their southern flank, young protesters were suddenly rallying thousands, and then tens of thousands, of their fellow citizens to demand the ouster of the regime, led by President Ali Abdullah Saleh and his family for 43 years.

Meanwhile, across a narrow expanse of water on Saudi Arabia’s northeast border, protesters in Bahrain rallied in the hundreds of thousands around a central roundabout in Manama. Most Bahraini demonstrators were Shiites with a long list of grievances over widespread economic and political discrimination. But some Sunnis also participated, demanding more say in a government dominated by the Al-Khalifa family since the 18th century.

Protesters deny that their goals had anything to do with gaining sectarian advantage. Independent observers, including the U.S. government, saw no sign that the protests were anything but homegrown movements arising from local problems. During a visit to Bahrain, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates urged the government to adopt genuine political and social reform.

But to the Saudis, the rising disorder on their borders fit a pattern of Iranian meddling. A year earlier, they were convinced that Iran was stoking a rebellion in Yemen’s north among a Shiite-dominated rebel group known as the Houthis. Few outside observers saw extensive ties between Iran and the Houthis. But the Saudis nonetheless viewed the nationwide Yemeni protests in that context.

In Bahrain, where many Shiites openly nurture cultural and religious ties to Iran, the Saudis saw the case as even more open-and-shut. To their ears, these suspicions were confirmed when many Bahraini protesters moved beyond demands for greater political and economic participation and began demanding a constitutional monarchy or even the outright ouster of the Al-Khalifa family. Many protesters saw these as reasonable responses to years of empty promises to give the majority Shiites a real share of power—and to the vicious government crackdown that had killed seven demonstrators to that point.

But to the Saudis, not to mention Bahrain’s ruling family, even the occasional appearance of posters of Lebanese Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah amid crowds of Shiite protesters pumping their fists and chanting demands for regime change was too much. They saw how Iran’s influence has grown in Shiite-majority Iraq, along their northern border, and they were not prepared to let that happen again.

As for the U.S., the Saudis saw calls for reform as another in a string of disappointments and outright betrayals. Back in 2002, the U.S. had declined to get behind an offer from King Abdullah (then Crown Prince) to rally widespread Arab recognition for Israel in exchange for Israel’s acceptance of borders that existed before the 1967 Six Day War—a potentially historic deal, as far as the Saudis were concerned. And earlier this year, President Obama declined a personal appeal from the king to withhold the U.S. veto at the United Nations from a resolution condemning continued Israeli settlement building in Jerusalem and the West Bank.

The Saudis believe that solving the issue of Palestinian statehood will deny Iran a key pillar in its regional expansionist strategy—and thus bring a win for the forces of Sunni moderation that Riyadh wants to lead.

Iran, too, was starting to see a compelling case for action as one Western-backed regime after another appeared to be on the ropes. It ramped up its rhetoric and began using state media and the regional Arab-language satellite channels it supports to depict the pro-democracy uprisings as latter-day manifestations of its own revolution in 1979. “Today the events in the North of Africa, Egypt, Tunisia and certain other countries have another sense for the Iranian nation.… This is the same as ‘Islamic Awakening,’ which is the result of the victory of the big revolution of the Iranian nation,” said Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Iran also broadcast speeches by Hezbollah’s leader into Bahrain, cheering the protesters on. Bahraini officials say that Iran went further, providing money and even some weapons to some of the more extreme opposition members. Protest leaders vehemently deny any operational or political links to Iran, and foreign diplomats in Bahrain say that they have seen little evidence of it.

March 14 was the critical turning point. At the invitation of Bahrain, Saudi armed vehicles and tanks poured across the causeway that separates the two countries. They came representing a special contingent under the aegis of the Gulf Cooperation Council, a league of Sunni-led Gulf states, but the Saudis were the major driver. The Saudis publicly announced that 1,000 troops had entered Bahrain, but privately they concede that the actual number is considerably higher.

If both Iran and Saudi Arabia see themselves responding to external threats and opportunities, some analysts, diplomats and democracy advocates see a more complicated picture. They say that the ramping up of regional tensions has another source: fear of democracy itself.

Long before protests ousted rulers in the Arab world, Iran battled massive street protests of its own for more than two years. It managed to control them, and their calls for more representative government or outright regime change, with massive, often deadly, force. Yet even as the government spun the Arab protests as Iranian inspired, Iran’s Green Revolution opposition movement managed to use them to boost their own fortunes, staging several of their best-attended rallies in more than a year.

Saudi Arabia has kept a wary eye on its own population of Shiites, who live in the oil-rich Eastern Province directly across the water from Bahrain. Despite a small but energetic activist community, Saudi Arabia has largely avoided protests during the Arab Spring, something that the leadership credits to the popularity and conciliatory efforts of King Abdullah. But there were a smattering of small protests and a few clashes with security services in the Eastern Province.

The regional troubles have come at a tricky moment domestically for Saudi Arabia. King Abdullah, thought to be 86 years old, was hospitalized in New York, receiving treatment for a back injury, when the Arab protests began. The Crown Prince, Sultan bin Abdul Aziz, is only slightly younger and is already thought to be too infirm to become king. Third in line, Prince Nayaf bin Abdul Aziz, is around 76 years old.

Viewing any move toward more democracy at home—at least on anyone’s terms but their own—as a threat to their regimes, the regional superpowers have changed the discussion, observers say. The same goes, they say, for the Bahraini government. “The problem is a political one, but sectarianism is a winning card for them,” says Jasim Husain, a senior member of the Wefaq Shiite opposition party in Bahrain.

Since March 14, the regional cold war has escalated. Kuwait expelled several Iranian diplomats after it discovered and dismantled, it says, an Iranian spy cell that was casing critical infrastructure and U.S. military installations. Iran and Saudi Arabia are, uncharacteristically and to some observers alarmingly, tossing direct threats at each other across the Gulf. The Saudis, who recently negotiated a $60 billion arms deal with the U.S. (the largest in American history), say that later this year they will increase the size of their armed forces and National Guard.

And recently the U.S. has joined in warning Iran after a trip to the region by Defense Secretary Gates to patch up strained relations with Arab monarchies, especially Saudi Arabia. Minutes after meeting with King Abdullah, Mr. Gates told reporters that he had seen “evidence” of Iranian interference in Bahrain. That was followed by reports from U.S. officials that Iranian leaders were exploring ways to support Bahraini and Yemeni opposition parties, based on communications intercepted by U.S. spy agencies.

Saudi officials say that despite the current friction in the U.S.-Saudi relationship, they won’t break out of the traditional security arrangement with Washington, which is based on the understanding that the kingdom works to stabilize global oil prices while the White House protects the ruling family’s dynasty. Washington has pulled back from blanket support for democracy efforts in the region. That has bruised America’s credibility on democracy and reform, but it has helped to shore up the relationship with Riyadh.

The deployment into Bahrain was also the beginning of what Saudi officials describe as their efforts to directly parry Iran. While Saudi troops guard critical oil and security facilities in their neighbor’s land, the Bahraini government has launched a sweeping and often brutal crackdown on demonstrators.

It forced out the editor of the country’s only independent newspaper. More than 400 demonstrators have been arrested without charges, many in violent night raids on Shiite villages. Four have died in custody, according to human-rights groups. Three members of the national soccer team, all Shiites, have also been arrested. As many as 1,000 demonstrators who missed work during the protests have been fired from state companies.

In Shiite villages such as Saar, where a 14-year-old boy was killed by police and a 56-year-old man disappeared overnight and showed up dead the next morning, protests have continued sporadically. But in the financial district and areas where Sunni Muslims predominate, the demonstrations have ended.

In Yemen, the Saudis, also working under a Gulf Cooperation Council umbrella, have taken control of the political negotiations to transfer power out of the hands of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, according to two Saudi officials.

“We stayed out of the process for a while, but now we have to intervene,” said one official. “It’s that, or watch our southern flank disintegrate into chaos.”

By BILL SPINDLE and MARGARET COKER