President Ali Abdullah Saleh is still resisting the popular clamor for his removal that has convulsed Yemen since protesters toppled Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak four weeks ago, but the odds are stacking up against him. About 30 people have been killed, mostly in the rebellious south, in clashes between Saleh’s security forces and the tens of thousands of protesters turning out daily across the country.

So far Saleh and his foes have avoided the bloody all-out battles for control such as those unfurling in Libya, where an equally determined Muammar Gaddafi is fighting for survival.

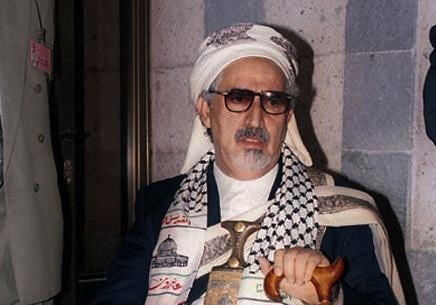

The Yemeni leader, who has ruled for 32 years by cannily navigating tribal politics, installing clan relatives in top security posts and rewarding loyalty with cash and favors, may be reluctant to go down the Gaddafi route, yet the prolonged standoff in the streets carries mounting risks of violence.

Police and security men fired into demonstrators near Sanaa University late on Tuesday, killing one and wounding 80.

“The events of last night illustrate that Saleh is willing to use increasing violence in an effort to maintain his rule,” said Sarah Phillips, a Yemen expert at Sydney University.

“The problem he has is that opposition to his regime is incredibly diverse, both geographically and in terms of what people want, after the immediate desire of seeing him step down, and that he now has very little that he can offer people.”

There is no sign of any let-up in the swelling protests against Saleh by Yemenis who blame him for what they see as decades of high-level graft, poverty and neglect.

“The momentum now is with the opposition, both protesters and the political parties, and that’s become increasingly clear,” said Shadi Hamid of the Brookings Doha Center.

“We saw the largest pro-democracy protests in Yemen’s history last week. We’re seeing more opposition unity.”

Saleh, already combating revolts in the north and south, as well as an ambitious al Qaeda wing, has been losing the support of once-allied tribal sheikhs, lawmakers from his ruling party and Muslim clerics, but the army and police still seem loyal and the president’s Saudi and U.S. allies have not deserted him.

The veteran leader may accept that he cannot extend his rule indefinitely. “At this time, the most he would hope for is to preside over a transition period until the end of his term in 2013,” said Yemeni political analyst Abdul-Ghani al-Iryani.

WAR CHEST

The 68-year-old leader, using what opposition MP Abdulmoez Dabwan calls a “war chest” of cash, can also bring out loyalist crowds in his defense — this week his party organized free lunches for hundreds who then joined a pro-Saleh demonstration.

Saleh has pledged to quit in 2013 and not hand power to his son, but rejected an opposition plan proposed last week for political reforms and a timetable for his departure this year.

Ali Omrani, a former member of Saleh’s party, said Yemenis were no longer satisfied with vague promises from the president.

“He needs to offer something very clear about the peaceful transfer of power. He has to start with the security services and make a gesture — at least begin removing his relatives.”

Saleh accuses his foes of threatening Yemen with chaos and portrays himself to the West as a bulwark against al Qaeda. His government this week asked foreign donors to stump up $6 billion to fund its budget deficits over the next five years.

“Yemen wants more money to come in and Saleh wants to really try and fragment and fracture the protesters,” said Gregory Johnsen, a Yemen scholar at Princeton University.

“He believes if he can do that, he can continue to survive. But a lot of the protesters are wise to the game… and are trying to stand in solidarity with one another,” he said, citing the so-called Houthi northern rebels and southern secessionists.

Saleh’s challenges have multiplied in recent years as oil and water resources dwindle in Yemen, an unruly land of mountain and desert where guns abound and central authority is lax.

“The inability of the central government to deliver basic public services, the absence of law and order and the fragmentation of society have created the ideal environment for autonomists, secessionists, insurgents and irredentists to emerge and flourish in many parts of the country,” said Khaled Fattah, at Scotland’s St Andrews University.

The protests feed off youth unemployment, hunger and corruption, but many of Yemen’s 23 million people are also fed up with an autocratic leader who denies them a voice — and are impatient with opposition parties trying to cut deals with him.

Hamid, the Brookings analyst, said Saleh’s strategy was to stall and promise dialogue without altering the fundamental structure of the system in hopes the protests lose steam.

“But I don’t think we should be under the illusion that Saleh is going to become a democrat overnight,” he added.

Iryani said Saleh’s entourage was probably pressing him to fight it out and if the power balance shifted in his favor he might even opt for Gaddafi-style force — although in Egypt and Tunisia the military refused to suppress popular protests.

“The army has not been tested against the people yet. When it does, I expect it to disintegrate quickly,” he said.

Source Reuters