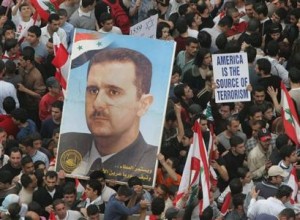

“Long live Al Jazeera!” chanted Egyptian protesters in Tahrir Square on Feb. 6. Many Arabs — not least the staff at Al Jazeera — have said for years that the Arab satellite network would help bring about a popular revolution in the Middle East. Now, after 15 years of broadcasting, it appears the prediction has come true. There is little question that the network played a key role in the revolution that began as a ripple in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, and ended up a wave that threatens to wash away Egypt’s long-standing regime.

“We knew something was coming,” Mustafa Souag, head of news at Al Jazeera’s Arabic-language station, told me Monday. “Our main objective was to provide the most accurate and comprehensive coverage that we could by sending cameras and reporters to any place there is an event. And if you don’t have a reporter, then you try to find alternative people who are willing to cooperate because they believe in what we are doing.”

The Tunisian uprising revealed that the dogma perpetuated by the country’s regime — that it was impregnable and its security services invincible — was merely propaganda aimed at keeping Tunisia’s people subdued. Al Jazeera shared this revelation around the region live and in real time, breaking the spell that had stopped millions of ordinary people from rising up and claiming their legitimate rights. Suddenly change seemed possible everywhere across the Middle East.

“We did not foresee the drama of events, but we saw how events in Tunisia rippled out and we were mindful of the fact [that] things were changing, and so we prepared very carefully,” said Al Anstey, managing director of Al Jazeera English. “We sent teams to join our Cairo bureau and made sure that we were covered on the ground in other countries in the region so when the story unfolded we were ready to cover all angles.”

Al Jazeera’s powerful images of angry crowds and bloody morgues undercut the Egyptian regime’s self-serving arguments and stood in sharp contrast to the state-run TV channels, which promoted such a dishonest version of events that some of their journalists resigned in disgust. At least one popular TV talk-show presenter, Mahmoud Saad, was later seen being carried on the shoulders of triumphant demonstrators in Tahrir Square. While Al Jazeera was showing hundreds of thousands of people calling for the end of the regime, Egyptian TV showed humdrum scenes of traffic quietly passing by; when Al Jazeera reported hundreds of people queuing for bread and petrol, Egyptian TV showed happy shoppers with full fridges using footage filmed at an unknown time in the past.

During the uprising in Cairo, the Egyptian government systematically targeted Al Jazeera in an attempt to impede the network’s gathering and broadcasting of news. On Jan. 27 Al Jazeera Mubasher, the network’s live channel, was dropped by the government-run satellite transmission company, Nilesat. On Jan. 30, outgoing Egyptian Information Minister Anas al-Fiqi ordered the offices of all Al Jazeera bureaus in Egypt to be shut down and the accreditation of all network journalists to be revoked. At the height of the protests, Nilesat broke its contractual agreement with the network and stopped transmitting the signal of Al Jazeera’s Arabic channel — which meant viewers outside Egypt could only follow the channel on satellites not controlled by the Egyptian authorities. To the rescue came at least 10 other Arabic-language TV stations, which stepped in and offered to carry Al Jazeera’s content. “They just volunteered,” said Souag. “They were not paid, and we thanked them for that.”

The next day, six Al Jazeera English journalists were briefly detained and then released, their camera equipment confiscated by the Egyptian military. On Feb. 3, two unnamed Al Jazeera English journalists were attacked by Mubarak supporters; three more were detained. On Feb. 4, Al Jazeera’s Cairo office was stormed and vandalized by pro-Mubarak supporters. Equipment was set on fire and the Cairo bureau chief and an Al Jazeera correspondent were arrested. Two days later, the Egyptian military detained another correspondent, Ayman Mohyeldin; he was released after nine hours in custody. The Al Jazeera website has also been under relentless cyberattack since the onset of the uprising.

“The regime did everything they could to make things difficult for us, but they did not succeed,” said Souag. “We still had the most comprehensive reporting of the events in Egypt.”

After the first few days of the uprising, the Egyptian state media began running an insidious propaganda campaign in an apparent effort to terrorize ordinary Egyptians into staying at home and off the streets. Channel 1 on Egypt state TV issued vague yet alarming warnings about armed thugs trying to infiltrate the protests and later broadcast live phone-ins in which members of the public complained about looting and disorder. It’s hard to think of a better way to incite panic in a jittery population, especially because there have been no emergency services in Egypt for days. By the time these garbled and unsubstantiated stories passed through the Egyptian rumor mill, ordinary people would be forgiven for thinking World War III had broken out. Egyptian state media have also issued warnings of international journalists with a “hidden agenda” and accused Al Jazeera of “inciting the people.” One supposed “foreign agent” was shown on Egyptian state TV with face obscured, claiming that she had been trained by “Americans and Israelis” in Qatar, where Al Jazeera is based.

But the lid on Pandora’s box has been prized open, and undemocratic regimes across the region are now looking over their shoulder at Al Jazeera — for history shows that where Egypt goes, other Arab countries soon follow. Given Al Jazeera’s enormous influence on the Arab street and its electrifying message that Arab dictatorships are, in fact, mortal, it is no wonder dictators and despots across the region have been left feeling rather rattled. There have already been hints of insurrection’s ripples in Algeria, Jordan, Yemen, and Bahrain. But could Al Jazeera threaten Saudi Arabia?

Oil- and gas-rich Arab states can use their wealth to address some of the grievances that brought Tunisians and Egyptians onto the streets, but not all. Al Jazeera’s home country, however, would appear to be somewhat safe from the wave of unrest. Power in Qatar is traditionally transferred by coup d’état, as in 1995 when the current emir, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, seized power from his father Sheikh Khalifa — but as the world’s richest country with a GDP per capita in excess of $145,000, it is highly unlikely to experience revolutionary convulsions about anything besides shopping. The most pressing socioeconomic problem the leadership currently faces is how to motivate a population of soon-to-be millionaires to keep showing up for work in the morning.

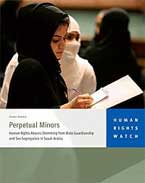

Helping to bring revolution to Egypt and Tunisia is one thing; fomenting uprisings in the Persian Gulf is quite another. But the situation is delicate in Saudi Arabia, where the regime is wobbling on the cusp of change. The kingdom either directly or indirectly controls most of the Arab media, including Al Jazeera’s principal rival Al Arabiya, but it remains highly vulnerable to the kind of palpitations Al Jazeera could easily provoke.

Bilateral relations between tiny Qatar and its overbearing neighbor Saudi Arabia have always been sensitive. Since 1996, when Al Jazeera first challenged Saudi hegemony in the region, the channel has been a constant point of tension between the two. For years, the Saudis dominated the Arabian Peninsula and often meddled in Qatari politics. On several occasions in the 1990s, the Saudis simply invaded Qatar to remind it who was boss and, following Sheikh Khalifa’s deposal, Riyadh tried to manipulate his return by organizing a countercoup.

But despite all the problems the Qataris have had with the Saudis, they are fully aware that if they upset the kingdom it is at their peril. As a result, coverage of Saudi affairs on Al Jazeera has not been as bold as coverage of Egypt and Tunisia. Issues of extreme sensitivity to the Saudi regime, such as royal family corruption and the succession question, are passed over lightly. Leading Saudi dissidents have rarely appeared on the network in recent years; there was, for example, next to no coverage on the Arabic channel of the 2010 murder in London committed by Saudi Prince Saud bin Abdulaziz bin Nasir al-Saud.

“Al Jazeera was absent from Saudi Arabia for a long time, so we don’t have pictures or information from within the country,” explained Souag. “Finally the Saudis allowed us to open an office about two weeks ago, and so we have a correspondent there now, and if there is something that needs to be covered we will report it in the same way as events anywhere else.”

It’s an issue of proximity and power. Despite the channel’s exceptional job in covering the turmoil in Tunisia and Egypt, the complex relationship with Saudi Arabia is a reminder that even for Al Jazeera, in the Persian Gulf free press has its limits. History will record the channel’s crucial galvanizing role in the extraordinary events that are now unfolding in Egypt and Tunisia. But whether the Al Jazeera effect will continue to ripple across the Middle East or the heavy hand of state pressure will attempt to shut Pandora’s box again — however temporarily — is yet too close to call.

By Hugh Miles