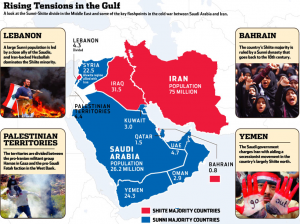

Saudi Arabia, the oil rich kingdom that is the birthplace and former home of Osama bin Laden, has staved off the widespread popular protests that have swept across the region since January. The country’s oil-rich Eastern Province, bordering Bahrain, has witnessed protests from the minority Shia Muslim population. In March, Saudi Arabia sent troops to Bahrain to support its royal family after a month of protests. We speak with Toby Jones, author of Desert Kingdom: How Oil and Water Forged Modern Saudi Arabia, on the role of Saudi Arabia in suppressing the Bahrain uprising, as well as its own. “We shouldn’t assume that there is a lack of interest on the part of Saudi citizens in achieving some sort of democratic or political reform. There are deep frustrations in Saudi society,” says Jones.

JUAN GONZALEZ: We turn now to Saudi Arabia, the oil-rich kingdom that is the birthplace and former home of Osama bin Laden. On Thursday, a senior extremist linked to al-Qaeda surrendered to Saudi authorities. Khaled Hathal al-Qahtani is thought to be the first operative to turn himself in after U.S. Special Forces killed Osama bin Laden on Sunday in Pakistan.

In recent months, Saudi Arabia has staved off the widespread popular protests that have swept across the region since January. The country’s oil-rich Eastern Province, bordering Bahrain, has witnessed some protests from the minority Shia Muslim population. In March, Saudi Arabia sent troops to Bahrain to support its royal family after a month of protests.

Seventy percent of Saudi Arabia’s almost 19 million people are under the age of 30, and last year unemployment was at 10 percent. In a bid to pacify Saudi citizens, King Abdullah, the 87-year-old head of state, has distributed over $100 billion in social handouts since February.

Municipal elections are planned for September. Women will not be able to run for seats or vote in the elections, and there have been some protests organized by women to end the Kingdom’s discriminatory laws. Saudi Arabia has no political parties.

To discuss the situation there, we’re joined by Toby Jones, assistant professor of history at Rutgers University. He was previously Persian Gulf analyst for the International Crisis Group. He’s the author of Desert Kingdom: How Oil and Water Forged Modern Saudi Arabia and is working on a new book project, America’s Oil Wars.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

TOBY JONES: Thanks for having me.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, why has Saudi Arabia escaped the widespread popular movements that have swept through the Middle East and the Arab world?

TOBY JONES: Well, for a number of reasons. The first is that it possesses the incredible ability to police its own population, which is not dissimilar from other autocratic regimes in the region. But it also has oil wealth and an almost unlimited ability to pay out, and to co-opt potential dissidence, which we saw the King and the royal family attempt to do in early and mid-March by passing out, as you noted, over $100 billion in inducements to encourage people not to take to the streets.

But we shouldn’t assume that there is a lack of interest on the part of Saudi citizens in achieving some sort of democratic or political reform, that there is absent in Saudi Arabia the political will for precisely the kind of thing that happened in Egypt or Tunisia, Yemen, Syria or Bahrain. There are deep frustrations in Saudi society. There are anxieties about the ailing nature of the political system, corruption within the royal family, and a deep desire to see fundamental change.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about how Saudi Arabia has repressed its own protests as well as moved into Bahrain to support the government in the fierce repression of the pro-democracy movement there?

TOBY JONES: Well, in addition to using financial and other kinds of social inducements to convince its citizens not to take to the streets, at least not for now, the Saudis have also rolled out a series of other measures, some security-based, initially responding to the possibility of a popular uprising in mid-March. The Kingdom blanketed its streets with heavy security presence, discouraging people from gathering publicly.

But they’ve also done another thing, which is very important and has not totally escaped notice but is important to keep in mind, particularly in light of the demise of Osama bin Laden and the continuing concern about the global war on terror: Saudi Arabia has also renewed a set of relationships with the religious establishment, empowering Islamists, as part of this wave of responding to popular mobilization, using the religious clergy and religious scholars to attempt to delegitimize popular protest and also to basically encourage citizens to remain quiescent. The reestablishment or the re-empowerment of the religious clergy is a new thing under King Abdullah. When he came to power in 2005, he actually took fairly serious measures to roll back the authority of the religious establishment, which he saw both as a source of embarrassment but also as a potential threat to Saudi power, to the power of the royal family. So the fact that some of his early efforts or some of his most recent efforts are being systematically undone and that the clergy are enjoying a kind renaissance, if you will, should be a source of concern.

The decision to intervene in Bahrain is linked directly to anxieties on the part of the Saudis about the potential for a democratic demonstration effect. They worry that if there were popular uprisings or if there was a successful regime change in Bahrain, that that might somehow sweep across the Saudi borders and encourage Saudi citizens to pursue a similar path. But there’s also another element, and that is something that is perhaps particular to the Saudis and the Bahrainis. There is a deep sense of anti-Shiism and sectarianism in the Kingdom. So, the specter of Shia political power in Bahrain, so soon after Iraqi Shias came to enjoy predominance and power in Saudi Arabia’s most powerful northern neighbor, was too much for the Saudis to bear. And so, they preemptively intervened, militarily occupied Bahrain, in order to stamp out the possibility of Shia empowerment there.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And the issue of the U.S. relations, especially in view of the fact that the continuing total lack of rights for women in Saudi Arabia, that our government never mentions a word about or talks about that—how is the Kingdom able in this age, with all the modern communications that we have, to continue to suppress the rights of women and yet receive virtually no condemnation anywhere in the rest of the world?

TOBY JONES: Well, they certainly don’t receive political condemnation from the powers that be here in the United States or elsewhere. And it has to do with the Kingdom’s ability to supply the quintessential industrial resource—right, its role—and not only just providing oil, but in being the most important global producer of oil on the planet. It has the ability to shape markets, to make up for shortfalls, to exceed capacity, everywhere, makes it more vital than lots of other places. And this has long been most important and the single most important political priority for American policymakers, and for Western policymakers more broadly. Women’s rights, in the grand scheme of things, then, from the perspective of the State Department or the White House, they almost hardly matter.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about Osama bin Laden and Saudi Arabia? You were talking about the empowerment of the clergy. Talk about his history. He is from Saudi Arabia.

TOBY JONES: Right. Well, his citizenship is contested by the Saudis, who claim that he’s actually Yemeni in origin. But his father was an important contractor in Saudi Arabia, ran a major construction business. He first came of age working for Aramco, the Arabian American Oil Company, in Saudi Arabia, but then became a main contractor to the Saudi state. And bin Laden was one of his many children and sort of came of age in the Saudi political system and education system, grew up in the 1970s and in the 1980s, in a moment when Saudi Arabia was renewing its Islamic credentials, partly in response to a crisis in late ’70s, re-empowering the religious establishment and encouraging a certain interpretation of Islam, a particularly kind of virulent one. Bin Laden took note, traveled from Saudi Arabia to Afghanistan to participate in the anti-Soviet jihad there, or at least to provide services, and was radicalized in the context of the Afghan jihad, returned to Saudi Arabia shortly after the conclusion of that war. In 1990 and 1991, actually offered his services and the services of the Mujahideen to the Saudi royal family to defend the Kingdom from Saddam Hussein, who had just invaded Kuwait. He was politely rebuffed, and then left the Kingdom and went to Sudan, eventually on his way to Afghanistan, where he formed al-Qaeda and began fighting the global crusade against—the global war against the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about the U.S. support for the Mujahideen and Osama bin Laden, when they were fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan, and then, of course, they set their sights back on the United States.

TOBY JONES: That’s right. I mean, al-Qaeda, bin Laden and the phenomenon of global terrorism and global jihad is the direct outgrowth of the Afghan jihad. So the United States made a strategic decision in the late 1970s under the Carter administration, and then a set of policies that was accelerated under Reagan, to equip and aid the Mujahideen in rolling back the Soviets and pushing them back out of Central Asia, for lots of reasons, but most importantly, as Carter articulated in 1980, because they were too close to the Persian Gulf. That was the site of our vital interests, and we were willing to do whatever necessary to protect them. So the decision to support the jihad and the Arab Afghans, as well as the Afghani Mujahideen, is the context from which al-Qaeda and bin Laden emerged, along with a whole host of other folks.

That first generation of al-Qaeda jihadis, beyond 9/11, who began carrying out attacks in Saudi Arabia and Morocco and elsewhere, were trained on the battlefields in Afghanistan and in the camps there. It would be—it’s not entirely right that the United States directly armed bin Laden. They armed lots of other bad guys who had relationships with bin Laden. It is entirely appropriate to see bin Laden—to understand both his credibility, his legitimacy and the sources of his radicalization as being a product of American policy in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

JUAN GONZALEZ: I want to go back to Saudi Arabia for one moment to talk about this whole issue of the government’s attempt to rehabilitate former fighters. Basically, it provides enormous leniency to those who turn in their weapons and agree to reintegrate into Saudi society. Could you talk about that, especially the numbers who have come from—those who have been released from Guantánamo that Saudi Arabia has accepted back and put into these reeducation programs?

TOBY JONES: Well, it’s remarkable. The Saudis, on the one hand, do in fact have—they fear the power of al-Qaeda to do harm, and they were confronted with al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in 2003, 2004 and 2005, began a campaign inside Saudi Arabia. AQAP now continues to exist in Yemen and would like very much to do harm to the Saudis. So the Saudis are nervous about the power of terrorists to continue to do damage inside the Kingdom, both to threaten the royal family but also to potentially undermine its economy.

But it’s taken the path of dealing with these forces and these individuals by—precisely by rehabilitating them, by putting them in facilities that attempt to indoctrinate them. They bring in established clergy to essentially reeducate these folks, rehabilitate them. They’re provided with various subsidies and services, and then they’re reintegrated into family life, and into social life more broadly. So it’s a kind of catch-and-release program for suspected or for real terrorists.

One of the interesting paradoxes here is that when the Saudi state arrests liberals—not terrorists, but folks who demand things like constitutional monarchy, the creation of a constitutional monarchy, women’s rights, an end to corruption—those folks are imprisoned, and they’re left to stay there.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, what Saudi Arabia is doing now? In the piece you wrote, “Counterrevolution in the Gulf,” you talk about it pursuing policies that could destabilize the whole Persian Gulf.

TOBY JONES: Right. Well, the intervention in Bahrain has got to be one of the most deeply troubling things that the Saudis—and they’ve done a lot of troubling things, right? But the decision to intervene, to militarily occupy Bahrain, has been justified. Although there are lots of different motives, it’s been justified as a response to what the Saudis claim is Iranian meddling. Much of the assumption—many Gulf Arabs assume, as do many American policymakers, that there are preternatural connections between Shias in the Arab world, whether they’re in Iraq, Bahrain or Iran, that because they’re co-religionists, they share a single political objective, and because we view Iran as the single most important bogeyman in the region, this matters. The Saudis have used this precisely to frame their intervention in Bahrain, that we’re taking out—we’re checking the possibility of Iran to establish either a fifth column or a front line so close to Saudi Arabia’s oil-producing region in the Eastern Province. So, by framing things both in sectarian terms and as a response to Iranian power, for which there is no evidence, the Saudis are in fact escalating and provoking a potential regional crisis.

AMY GOODMAN: Toby Jones, I want to thank you for being with us, assistant professor of history at Rutgers University, previously with the International Crisis Group, a political analyst of the Persian Gulf, author of Desert Kingdom: How Oil and Water Forged Modern Saudi Arabia.